What Are Data-Driven Weather Models and Why Do They Matter?

For decades, weather forecasting has relied on physical simulations run on powerful supercomputers. These numerical weather prediction (NWP) systems simulate the atmosphere by solving fundamental physical equations, such as the Navier-Stokes equations, over a global grid, evolving forward in time step by step. These simulations are computationally intensive but provide reliable forecasts up to several days ahead.

A similar approach exists in climate science. In the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6), hundreds of climate models from research institutions worldwide generate projections over the coming century. These models simulate the Earth system by solving coupled physical equations for atmosphere, ocean, sea ice, and land, across millions of grid cells and time steps.

In recent years, data-driven methods have come to the forefront of weather modelling. Major tech companies, including Google, NVIDIA, Huawei, and Microsoft, have released ML-based models that match or even surpass traditional NWP performance in some areas. Importantly, in its 2021 machine learning roadmap, the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) itself recognized the growing relevance of ML methods and emphasised the need to integrate them into future forecasting systems.

So why is this shift happening now? A major advantage of the current era is the abundance of publicly available datasets. Organisations like ECMWF (with its ERA5 dataset), the CMIP6 initiative, and many others have made large volumes of global weather and climate data publicly available. The ERA5 dataset, for example, offers hourly, global atmospheric data from 1950 to the present at fine spatial and temporal resolution. These datasets are key enablers of modern data-driven modeling. At the same time, important open-source programming libraries, like PyTorch, have lowered the barrier to entry, making it easier to build and train sophisticated models.

To appreciate why this is such a big shift, it helps to understand what’s actually happening inside these models.

What are data-driven models?

Data-driven weather models are machine learning systems, typically deep neural networks, trained to predict future weather based on historical data. The most common training dataset is ERA5. “Training” here means adjusting the model’s parameters (weights and biases for neural networks) so that its predictions get closer and closer to the real data, measured by how far off the predictions are, using something called a “loss function”, which is often the root mean squared error (RMSE).

One way to think about this is that each combination of parameters in a neural network represents a different function. The training process searches for the best function to approximate the data. If successful, we say the model is optimized.

Crucially, these models are “data-driven” because they impose no explicit physical constraints. For example, in traditional physics-based models, conservation laws, like the conservation of energy, are essential constraints built into the system. Without such constraints, the model might, for instance, output more water from a cloud than was originally present. In the case of data-driven models, these constraints are not built into the system. These models have no built-in understanding of physics. Instead, they learn patterns purely from the data.

For this reason, there is no guarantee that our data-driven models will respect basic physics. They might optimise the loss function really well, but when making predictions based on previously unseen data, they perform horribly (this is called overfitting). Instead, we expect that the optimal function found through training will respect the underlying physics. However, this is not obvious and has to be verified separately. A lot of research has gone into this.

Pros and Cons

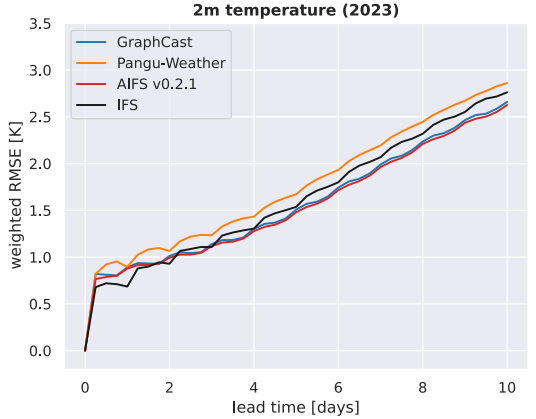

One of the main strengths of machine learning models is their ability to capture complex, nonlinear relationships (something the Earth system is full of). This is why they have shown great promise, especially in medium-range forecasting (3–10 days), where traditional models begin to lose accuracy. Machine learning weather models wouldn’t be getting so much attention if their performance wasn’t competitive with NWPs. Various models have shown superior or comparative performance in terms of metrics such as RMSE and ACC when compared to NWP models. The image below from Rackow et al. shows performance in terms of RMSE (the lower the better) at different lead times for three ML models against an NWP (IFS).

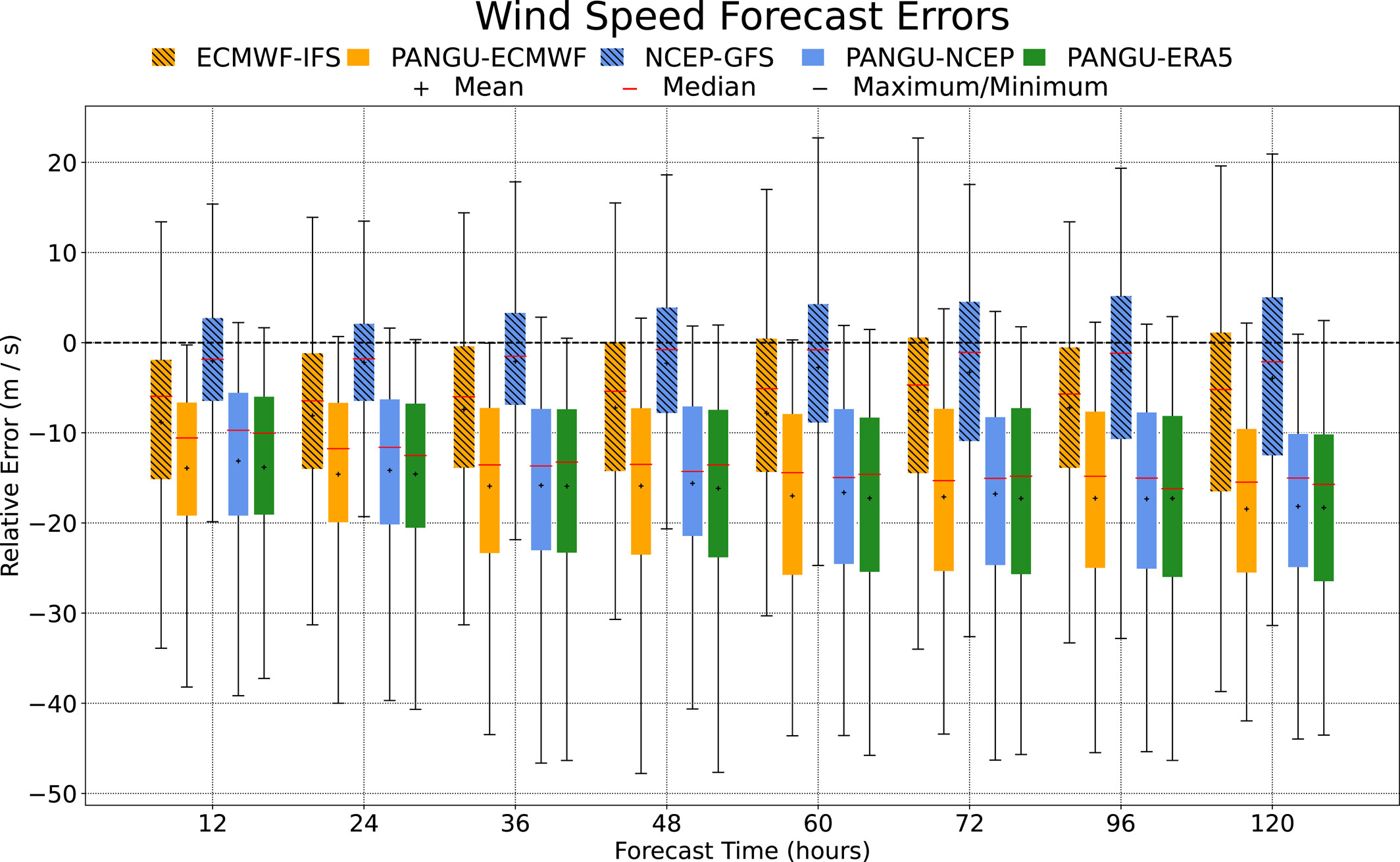

However, machine learning models require large amounts of data to be effective. Their performance often degrades in data-sparse regions or for rare and extreme events. In particular, studies have shown that ML models often underestimate the intensity of cyclones and other high-impact phenomena. The below figure from Shi et al. demonstrates this by showing the relative error of maximum wind speeds for a well known data-driven model, PanguWeather (PANGU-ECMWF, PANGU-NCEP, PANGU-ERA5; the same model with different initial conditions). It can be seen that compared to the other NWP models, PanguWeather has greater error (closer to zero is better), and greater dispersion.

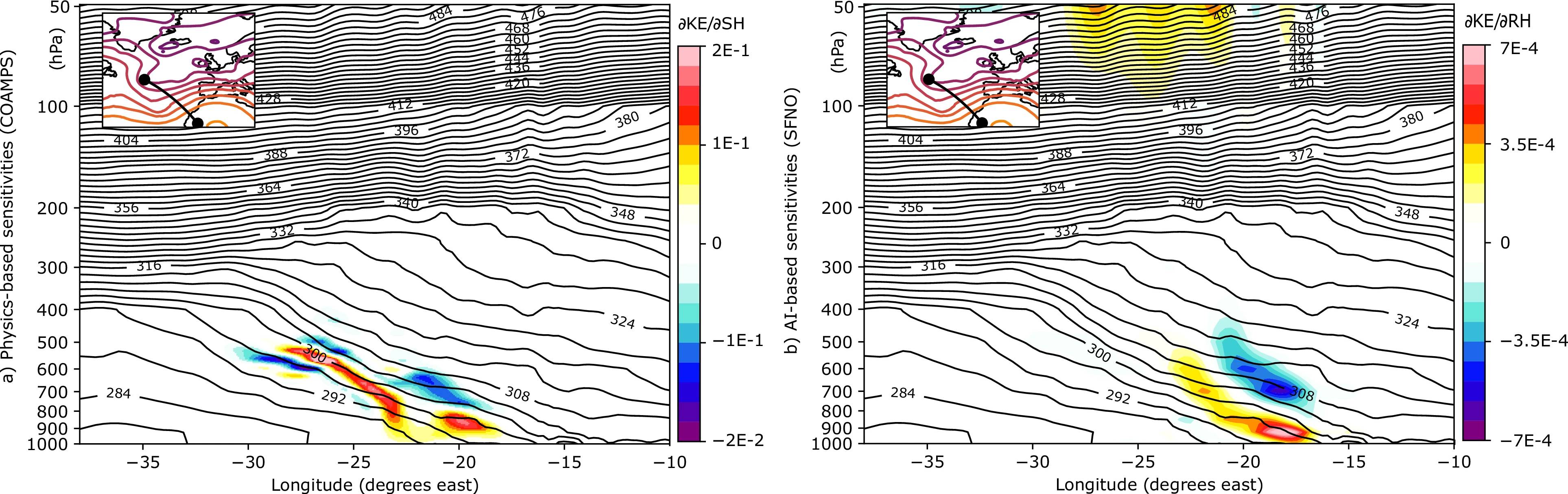

Physical interpretability is another challenge. Unlike physics-based models, where each variable and equation has a clear meaning, neural networks are often black boxes. And while some studies suggest that these models learn physically meaningful structures, it’s also been shown their internal representations of physical systems may be lacking. For example, the ML model studied by Baño-Medina et al. was shown to exhibit unexplained sensitivities to certain perturbations. In the below image, the figure on the right are the sensitivities from a NWP model and the figure on the left are the sensitivities from a data-driven model. The similarities near the bottom between the two are relatively good, supporting the notion that physical dynamics have been learnt. However, at the top of the left figure, sensitivities are observed not seen in the NWP one. There are also no known dynamics to explain this, suggesting that the ML model responded to perturbations that had no clear physical cause.

Other studies have noted that ML models tend to smooth out sharp gradients, reducing their practical resolution. In the study by Bonavita, it was noted that the “effective resolution” of the data-driven model is lower than the resolution of their input data. For instance, a model trained on ERA5 data at 0.25° resolution (~25 km) may produce outputs that are effectively closer to 1° (~100 km) or even coarser. Think of it like watching a 4K video that’s been blurred. While the file is high-res, the model ‘sees’ it more fuzzily.

Despite these issues, the most significant advantage that data-driven models have over traditional ones is that they are very fast to provide predictions. While training can take several weeks, possibly months, once training is complete, generating predictions can take seconds on a single GPU, and minutes on a CPU. This is in contrast to NWP models that can take up to several hours. Many of these models are open-source and easy to run, making them widely accessible.

Some of the Big Ones

Several notable ML weather models have emerged in recent years:

-

FourCastNet (NVIDIA, Feb 2022): Introduced a transformer-based model capable of ultra-fast global forecasts at high resolution. It emphasized speed and scalability, and later versions addressed robustness and interpretability.

-

Pangu-Weather (Huawei, Nov 2022): Developed a hierarchical transformer model that set new records for forecast accuracy across multiple lead times, outperforming ECMWF forecasts in many metrics.

-

GraphCast (Google DeepMind, Dec 2022): Used a graph neural network approach to model spatial and temporal dependencies. It demonstrated superior performance to traditional NWP on many skill scores.

-

Aurora (Microsoft, May 2024): Focused on high-speed forecasting at 0.1° resolution, Aurora integrates multiple innovations including adaptive attention and efficient training schemes.

Deep learning is transforming how we predict the weather. These models are already showing strong performance on traditional forecast metrics, often with a fraction of the computational cost. Their ability to quickly generate forecasts opens new possibilities, from faster global predictions to more accessible local insights. However, many challenges still remain. Issues around physical interpretability, resolution, and handling extreme events need to be addressed before these models can fully replace physics-based systems. Much research is going into closing these gaps.

In future posts, I’ll explore the architectures, breakthroughs, and open questions that are shaping the future of weather prediction.